Keeping the beat: How to heal the human heart

February 27, 2018

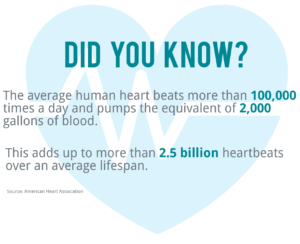

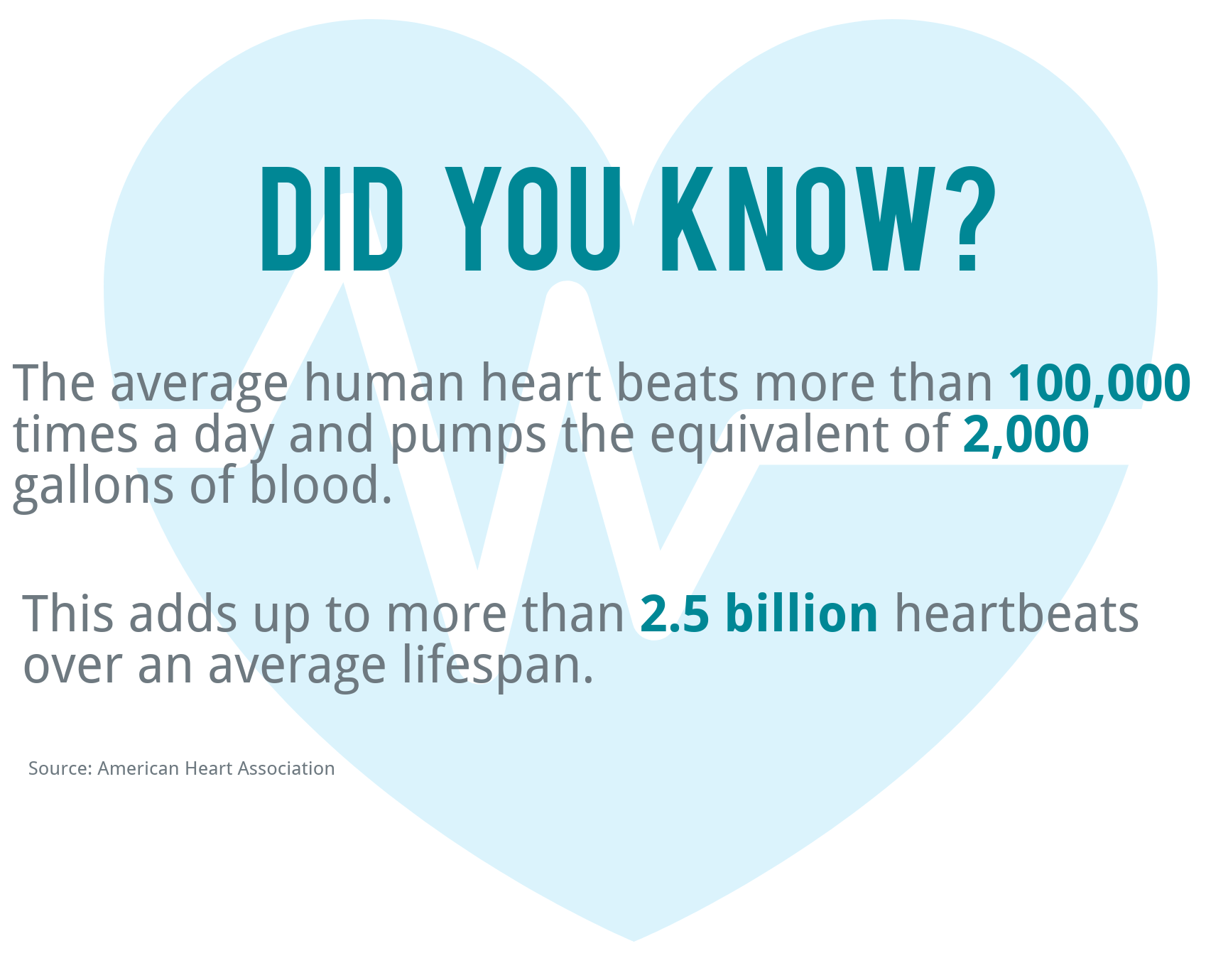

Our hearts beat to their own drum, the result of carefully regulated electrical impulses that ensure blood keeps pumping through our bodies.

Occasionally though, something goes wrong, causing the heart’s rhythm to become irregular, too fast or too slow. The result is a condition called arrhythmia, which can become a chronic problem with devastating consequences, often necessitating surgical intervention.

But what if there was a way to help the heart get itself back on track? According to Dr. Stefan Jovinge, director of Van Andel Research Institute and Spectrum Health’s DeVos Cardiovascular Research Program, the answer may lie within the heart itself.

A cardiac conundrum

Few systems are infallible, and the heart—and the specialized pacemaker cells that regulate heartrate—are no exception. If an arrhythmia becomes serious enough and can no longer safely be managed with medications and lifestyle changes, surgical implantation of a mechanical pacemaker often is the next option.

Unlike other cells in the body, such as those in the skin, heart cells do not simply regenerate when they become defective or after an injury such as a heart attack. Instead, it was long believed that once the organ reached its adult size, heart cells cease replicating, rendering the heart incapable of healing.

That all changed a few years ago, when a team led by Jovinge and his collaborators showed that adult heart cells do have the potential to reproduce and could possibly be coaxed into doing so, repairing the heart in the process. This paradigm shift has led scientists to look beyond mechanical pacemakers to something closer to home—biological pacemakers.

While this would be a big breakthrough for adults, it would be especially advantageous in children and teenagers, whose hearts are still growing. A biological pacemaker that can grow right with them could make all the difference, Jovinge said.

“What we’re really trying to do is help the heart help itself,” Jovinge said. “Mechanical pacemakers were a game-changer but now it’s time to take the idea further. Our hope is to use a person’s own cells to create a biological pacemaker that better integrates with the body, actually healing the heart rather than simply treating symptoms.”

Restoring rhythm

Jovinge’s approach uses induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are derived from adult cells (such as those from skin or blood) and are reprogrammed to an unspecialized, immature state. From there, his team can further program iPSCs into many different kinds of mature cells, including new pacemaker cells for the heart.

Ultimately, Jovinge envisions these new pacemaker cells being part of a tiny, biological patch—a sort of cellular bandage—that would integrate with the heart, replacing dysfunctional cells and bringing an irregular heartbeat back into balance.

The next step is to test the team’s plan in more complex lab models. If successful, they could potentially move on to clinical trials, which are critical steps on the road to bringing a new therapy to patients.

“We still have a way to go, but our results to date are very encouraging,” Jovinge said. “Biological pacemakers have the potential to shift the paradigm on how we view and manage cardiac conditions. If successful, they would be nothing short of life changing.”

There are many different types of arrhythmia—some cause the heart to beat too fast for too long (tachycardia), while others cause it to beat too slowly (bradycardia). They can range in severity from a one-time stress-induced flutter to a chronic, debilitating condition marked by a permanent change in the electrical signals that regulate heartbeat.

The most common type of arrhythmia is atrial fibrillation, or AFib for short. It occurs when the upper two chambers of the heart beat out of sync, interfering with blood flow into the lower two chambers. It’s estimated that between 2.7 and 6.1 million people in the U.S have AFib; sadly, about 130,000 deaths each year in the U.S. are linked to the condition.

Regardless of type, all arrhythmias are caused by problems with the heart’s electrical system, which is originates in a small area rich with specialized pacemaker cells called the sinus node. From there, electrical pulses spread from the top of the heart to the bottom, causing the muscle to contract propelling oxygen- and nutrient-rich blood throughout the body. A whole host of problems can interfere with this critical electrical switchboard, ranging from factors as mundane as aging to something more traumatic like a sudden injury.

February is American Heart Month. To learn more, visit here or follow along on social media with #movewithheart.