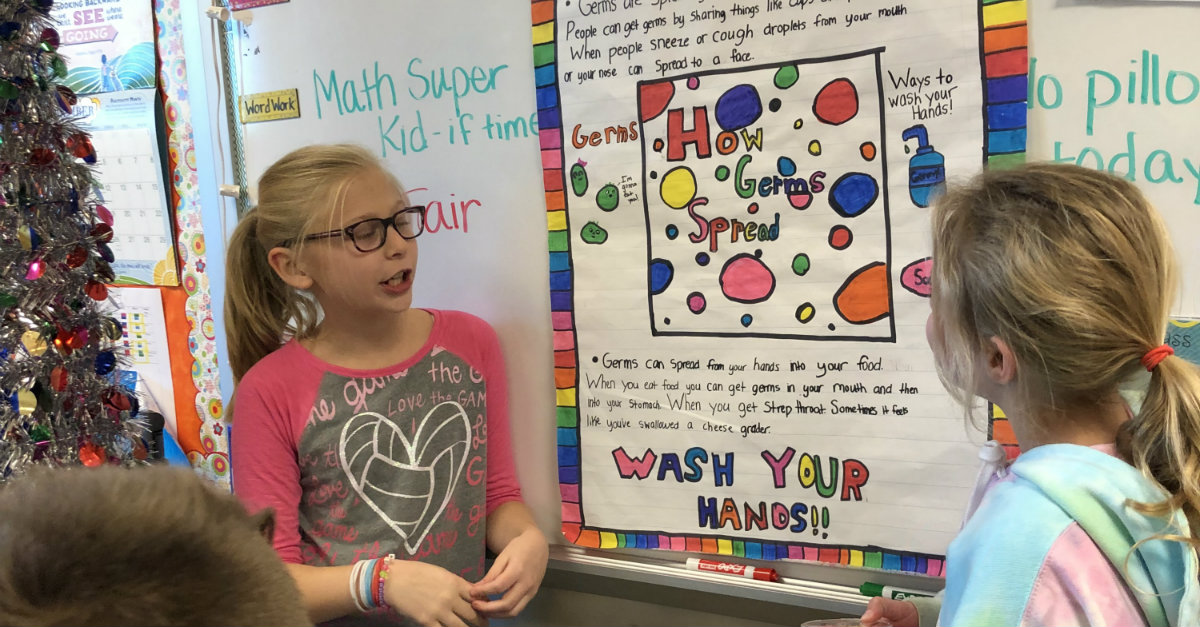

“But why?”

If you’ve ever worked with children, this question is sure to set off plenty of alarm bells. You know exactly where this conversation is headed. You can see it barreling toward you like a freight train at full speed. Yet, no matter how you answer, the child will always follow-up your response with another, “But why?”, “But why?”, “But why?” It’s like getting caught in a time loop.

Still, there’s a grain of wisdom to be gleaned from this exasperating experience. Children are curious by nature, and the way our culture answers questions has drastically changed. Teachers were once the best resource for disseminating knowledge. Now, Siri, smartphones, and high-speed internet have cornered the market on information. “But why?” has transformed into a much bigger question.

As educators, it’s our responsibility to help students discover the “why” in “but why?” Answers mean nothing if you don’t understand them. It’s important that students not only understand their conclusions but recognize how those conclusions were reached. You can accomplish this through a learning process called CER: Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning.

The Claim

All knowledge begins with a claim. In technical terms, a claim is a statement which answers an investigation question. This may sound simple, but in practice, it gets a little complicated. This is partially because students don’t always make claims which answer the investigation question they’re pursuing. For example, if the investigating question read:

“What is the effect of the number of turns of wire on the strength of an electromagnet?”

A proper claim would sound something like:

“I claim that increased strength of the electromagnet is a result of increasing the number of windings around the nail.”

Answers which deviate from the main point of the lesson (such as hypothesizing that the wires will melt or snap) can be useful but don’t address the actual question. When helping students write a claim, remind them to always connect back to the question.

The Evidence

Once a student’s claim has been established the next step is to have them refer to their evidence. Evidence comes from analyzed data that is appropriate (specifically addresses the claim) and sufficient (enough analyzed data) to support their claim. Or, in layman’s, this means that their data should come from reliable sources and fair testing.

One helpful method for ensuring this happens is to have your students make meaning of their data by using a four-part data analysis prompt:

- Evaluate – Determine whether the data they are working with is trustworthy. This requires checking sources for possible bias and subjecting the evidence to repeated testing.

- Organize – Work with the data. Have students lay out their observations in a way that makes sense to them. They organize their data to help reveal patterns and trends. It may involve math (averaging, equations, etc..).

- Represent – Display the data. This is great place for students be creative. Allow your students choice in how they communicate the patterns and trends they identified.

- Interpret – What is the evidence telling them? What does the data mean? This will become their evidence to support their claim.

The Reasoning

Your students have made a claim. They have assembled their evidence. Now, it’s time for them to defend their findings. The reasoning process is all about constructing an argument which shows how their evidence supports their claim. This breaks down into two parts;

Part 1: How was the evidence generated?

Have your students talk about how they conducted a fair test or what process they used to collect their data. The reason to do this is because we want kids to be creating their argument (and understanding their answers) around the quality of evidence they have generated to support their claim. The only way to accomplish this is by actually diving into the investigation and pulling out the solid facts. As a bonus, this process can also help your students develop confidence by having them to defend their findings.

Part 2: How does the science support your evidence and claim?

Again, for students to find support for their evidence, they need to interact with the science knowledge. This means familiarizing themselves with science theories, principles, and laws to support their conclusions. Remember, the students should always be the one doing the heavy lifting. This may sound like a lot of work to put on one pupil, but don’t let yourself be intimidated. Part of being an educator requires having confidence in your students and in the investigation. The work won’t be easy and the lessons my require refinement, but your students do have what it takes to tackle the scientific process.

There’s a whole journey of discovery waiting for them behind the question, “But why?” Get them started!

What about you? How do you build your students’ understanding of claim, evidence, and reasoning? Feel free to share your strategies in the comments below!

Content for this blog was drawn from the webinar Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning: Building Student Skills and Confidence in Developing Scientific Explanations with Marty Coon.